“Post proofs that brotherhood is not so wild a dream as those who profit by postponing it pretend.” — Norman Corwin, 1945

“Post proofs that brotherhood is not so wild a dream as those who profit by postponing it pretend.” — Norman Corwin, 1945

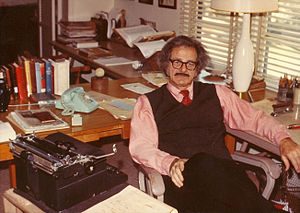

My friends often tell me I “kick myself” way more than I ought to. And they’re right. But one “kick” that’s still justifiable is the one I keep administering for not being able to find a way to get to California last year for the 100th Birthday Celebration of one of the most influential voices in Radio...Norman Corwin. As it turned out, I would have been able to sit down with Mr. Corwin and my college friend, Richard Fish, for a private visit which stretched from a promised “few minutes” into nearly three hours.

Note I capitalized Radio. That’s to differentiate the state of Radio in what’s now so quaintly termed its Golden Age from what it’s degenerated into.

But lest you think Norman Corwin was some kind of extraordinary voice actor, perhaps I should clarify. While he was an on-air voice and had a career on mic as well as off, his influence on what Radio was capable of doing lay in his imaginaton and his writing and his ability to instill in his various voice casts the spirit of what he created on the pages of his scripts. He knew how to direct those actors, along with countless technicians, musicians, even composers as accomplished as Bernard Herrman, in bringing his imaginings to life on the air…and have them re-created in the imaginations of his audiences.

Corwin could easily be dismissed by some as “high brow”. His love and mastery of language was on display in everything he wrote. But he could just as easily write in the voice of (pardon the over-used phrase) the common man. And he did so with such regularity that his various Radio series and specials were highly acclaimed, even though they were mostly “sustaining”…meaning they did not rely on comercial sponsors. Indeed, if you’ve read any of the current obituaries, you may note one his most famous broadcasts during the era of WWII was broadcast live on all three national networks.

But Norman Corwin could just as easily turn out a touching fairy tale story…like “The Odyssey of Runyon Jones”, about a little boy’s journey through a hell of a heavenly bureaucratic maze as he tries to free his little dog, unjustly sentenced to “Currgatory”. One of his first nationally broadcast plays was a pre-Dr. Seuss rhyming Christmas story, “The Plot to Overthrow Christmas”, with historical villains teaming up with the Devil to kidnap Santa and do away with him, long before Jack Skellington.

There was the uproarious (as least to me) show, “The Undecided Molecule”, where said molecule was put on trial for refusing to meekly be assigned his place in the universe. That showcased many top stars who would always be glad to appear in a Norman Corwin production: Vincent Price as the Prosecutor, Robert Benchley as the Defense Attorney, and as the wise-cracking Judge…Groucho Marx. Corwin’s writing was so precise that in listening to a recording of the broadcast, I had to stop myself mid-chuckle at what I thought was a Marx ad-lib…when the next rhyming line proved conclusively it had been in the script all along! And the Molecule itself was performed live by a sound effects man practially torturing a wave oscillator, decades before Ben Burtt came up with the sounds of R2-D2.

It wasn’t all fun and games, though. One program I rarely read about, but which chilled me when I first heard the recorded broadcast, was called “They Fly Through The Air With The Greatest of Ease”. It starts out as what you’d expect from some standard glorification of daring aviators, taking to the skies in their bombing runs. But part way through, there’s a horrifying shift of focus as the narrative suddenly follows the bombs down to the people they’re about to obliterate…not the ones you would have thought at the start of the program.

Corwin defied catagorization in his work. While it’s true he did some of his finest writing and producing in the truest flag-waving traditions of the 30s and 40s, he was sensitive to injustice no matter what its origin. This week’s Los Angeles Times article cites a program in the late 40s in response to the House Committe On Un-American Activties (the McCarthy communist witch hunts which ruined so many lives). In it, a narrator (actor Frederic March) spoke these words: “Who comes after us? Is it your minister who will be told what he can say in his pulpit? Is it your children’s school teacher who will be told what she can say in a classroom? Who are they after? They are after more than Hollywood. This reaches into every American city.”

He was still writing, still producing, even as he approached 100 years of age…with projects involving actors such as Jack Lemmon, Jessica Tandy, Martin Landau, Ed Asner, (Firesign Theatre’s) Phil Proctor, even William Shatner.

Norman Corwin understood media. And not just radio. While he is justly remembered for his Oscar-nominated work on the Kirk Douglas bio-pic on Vincent Van Gogh, “Lust for Life”, he was early on the director of a Radio play based on Archibald MacLeish’s “The Fall of the City”. While it boasted a voice cast including Orson Welles and Burges Meredith, live orchestra (again) conducted by Bernard Herrman…it is said that Corwin, in order to get just the right feel of the raw power of the mindless crowds (the Masterless Men of MacLeish’s story), had various sized groups of actors set up in a remote location at a local armory, where he directed their “crowd responses” like a conductor throughout the show, rather than having to rely on stock recorded crowd sound effects.

So, yeah. I guess I can be forgiven for kicking myself just a little bit for missing the chance to sit down with this titan of imagination. But, as I wrote last year when I told you to send him birthday card…I really sort of did meet the man, at least through his words and his work.

If you’ve ever created something with voices or sounds or music…and their respective languages…you’ve built on foundations set down by Norman Corwin, whether you knew it or not.

You can learn more about this man’s remarkable career in a book, written by one of my favorite college professors (and I only had a couple of good ones), R. Leroy Bannerman’s Norman Corwin and Radio: The Golden Years, plus Corwin’s own published works, still in print.

— over and out —